What is mastery, anyway?

My definition is different. And for athletes, it’s decidedly better.

Words are invented by people. We often forget this, arguing about the “true meaning” of words as though each and every noun, verb, and adjective was created by God at the beginning of time and discovered by man eons later. The reality is that words have no meaning beyond what is ascribed to them at a given time through the general consensus of its users.

Consider the English word “nice”. In the 1300s, it meant “foolish”. By the 1900s, however, its meaning had changed to “friendly”, and in the present century “nice” can also mean “terrific” (as in, “Nice way to end the season!”). I’m sure there was a time when grammar cops scolded people for using the word to denote anything other than “foolish”, but nobody remembers them. With language, the majority rules and the holdouts die off.

“Mastery” is another word whose meaning is often debated. Merriam-Webster defines it as “possession or display of great skill or technique,” but some people take issue with this meaning. In a 2023 blog post, former world champion mountain biker Sonya Looney argued that “the true meaning of mastery” is “practice”—a mindset-driven commitment to a path of improvement.

Looney is wrong to believe that “mastery” or any other word has a true meaning, but like everyone else she has the right to adopt any meaning she likes for a given word (or invent a whole new word, for that matter) and see if it catches on. Somebody somewhere was the very first person to use “nice” to mean “friendly,” and though they were completely outnumbered at the time, they got the last laugh.

I myself use the word “mastery” differently than most, and I would very much like my definition to catch on, at least among endurance athletes. Here goes:

My Two Cents

Let’s go back to Merriam-Webster’s definition of “mastery” as “skill”. Can these two words be used interchangeably? Not always. Consider the example of a 10-year-old girl who runs a 6-minute mile in her first attempt at the distance. If I reacted to this performance by saying, “Susie showed great skill as a runner,” you wouldn’t bat an eye. But if instead I said, “Susie demonstrated a mastery of running,” you’d object on the grounds that it makes no sense to say a person has mastered a sport they’ve only just begun to practice, regardless of how well they perform on first exposure.

What this example shows is that “mastery” refers not to skill in general but to skill that has been developed through practice. This is why “mastery” has a verb form and “skill” does not. Suppose Susie goes on to win the Millrose Games Wannamaker Mile three years in a row in her 20s. At that point, we might say she has mastered the mile distance, indicating that she has developed her skill to the maximum and reached her full potential as a middle-distance runner.

Is Talent Required for Mastery?

What we call “talent” blesses those who have it with a head start on the developmental curve, but it does not guarantee development. Likewise, an athlete without talent has the same opportunity others have to develop their skills to the maximum, reaching their full potential. Based on the distinction we’ve drawn between skill and mastery, it’s fair to say that an untalented athlete who reaches their full potential has mastered their sport to a greater degree than a talented athlete who has failed to fully develop their skill, even if the talented athlete performs at a higher level.

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the English word “master” comes from the Old French word maistrie, which meant “a state or condition of being a master; control, dominance.” The element of control has been a consistent thread in all definitions of “mastery” since the 13th Century. When a TV sports analyst says that a baseball pitcher has mastered a certain pitch, they mean that the pitcher has almost total control over the speed, spin, and direction of the pitch, so that it comes out the way the pitcher wants it to almost every time.

Obviously, not every athlete can achieve such control, even when they’ve developed their skill to the maximum. A certain amount of talent is required to perfect any technique. But although talent confers a kind of control that no amount of development can replicate, talent itself is outside an athlete’s control.

Controlling the Controllable

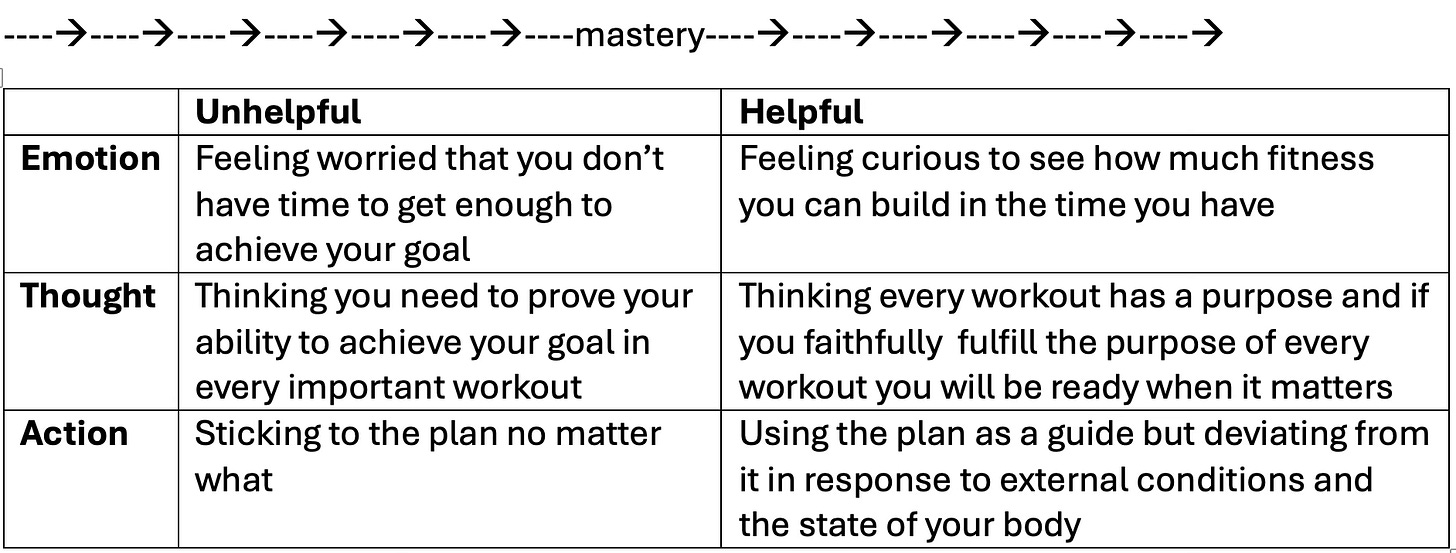

My definition of “mastery” separates the things an athlete can control from those they can’t and excludes the latter. As I see it, athletes master their sport to the extent that they fulfill their potential by gaining control of the controllable factors in their development. Every single day, athletes think, feel, and do things that either aid their development, impede it, or have a neutral effect. All athletes, regardless of talent, start the developmental process thinking, feeling, and doing lots of things that impede their development. But as they develop, they gain greater and greater control over their sport-relevant thoughts, feelings, and actions, eventually reaching a point where unhelpful thoughts, feelings, and actions have been virtually eliminated from their athletic lives.

And that, my friends, is mastery.

The grid above illustrates this process of developing athletically by learning to control the controllable. Don’t get too caught up in the specific examples I’ve given. There are countless other examples of specific emotions, thoughts, and actions that are either helpful or unhelpful to an athlete’s development. Your goal as a mastery-seeking athlete is to achieve general movement toward taking control of the factors you can control and using this control to keep your individual feelings, thoughts, and actions on the helpful side of the ledger.

Easy, right? Of course not. But what I like about this view of athlete development is that it make mastery attainable for every athlete—including you—and not just the Susies of the world.