Tom Fitzgerald’s Nontoxic Masculinity

My father’s new novel offers insights into how I was raised.

Road to Redemption, a new novel by Tom Fitzgerald (who happens to be my father), is about mortality, running, and yes, redemption. But it’s also about manhood and masculinity.

The protagonist, Cooper McKenzie, is a sensitive soul who dreams of “creating something beautiful” and being reincarnated as a chickadee. Bullied mercilessly as a boy by a sadistic older brother and an alcoholic father, Cooper takes a dim view of the male sex. Yet he’s manly in his own way, completing a series of marathon swims alone in the frigid waters of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River before joining the navy and undergoing SEAL training.

In an early scene, Cooper is standing on a beach on Coronado Island, where he is about to run a timed four-mile run, receiving final instructions from one Lieutenant Knowles, a testosterone-soaked commanding officer who embodies everything Cooper despises about men:

The lieutenant’s polished black boots were neatly trimmed at the top with the overflow of woolen socks worn only by Navy SEALs. Half his face was hidden behind a pair of mirrored aviators, epitomizing the manner and stance of one who can tolerate not so much as a glimpse of a rival anywhere in his proximity—chin slightly uplifted, feet slightly spread, hips tilted forward—in a posture intended to hint at the ferocity of the dragon that dwelled within.

I should note that Road to Redemption is highly autobiographical. That four-mile timed run on Coronado Island really happened in Tom’s actual life, and I can attest that my dad loathes machismo every bit as much as Cooper does. Throughout my childhood, my father never missed a chance to mock the Lieutenant Knowles types we encountered. “Big engine, small penis,” he’d say on the freeway as a leather-clad beefcake roared past us at deafening volume on a Harley-Davidson with ape-hanger handlebars.

My dad never uttered the term “toxic masculinity,” which originated in the mythopoetic men’s movement of the 1980s, coinciding with the thick of my journey from boyhood to manhood, but that’s exactly what he was mocking. The trait most commonly associated with manliness is strength, and Tom has no problem with that. He just happens to believe that the stronger a man is, the less effort he puts into projecting strength. In those days, Tom himself drove a freaking Renault Le Car, arguably the most unmanly automobile ever sold. Talk about having nothing to prove!

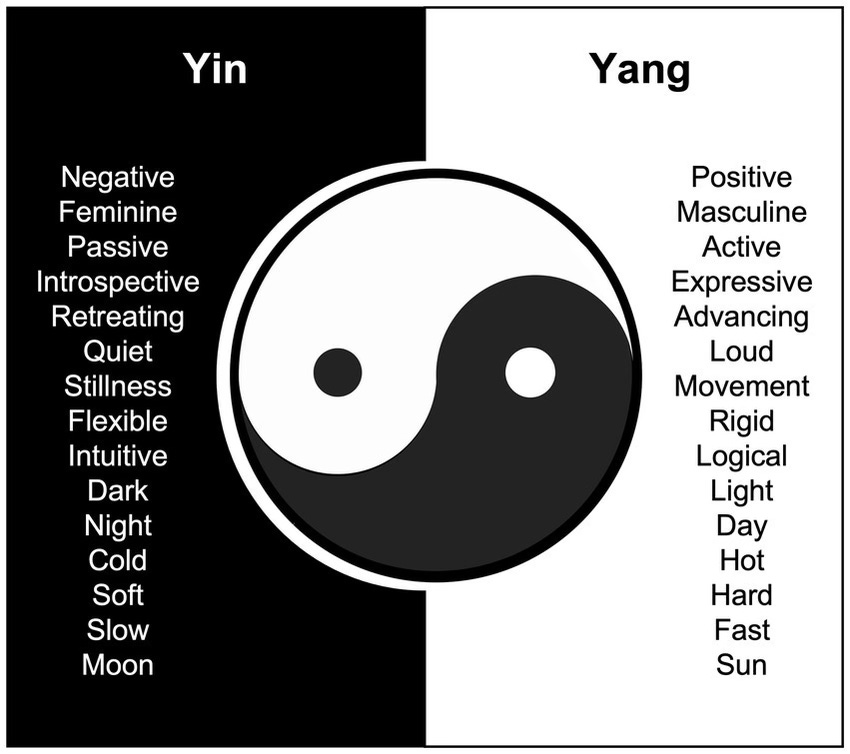

I never heard my father refer to himself as a feminist, either, but he didn’t have to; the proof was all over his writing. In Food 4 Thought, a collection of original aphorisms, there’s a whole chapter on men and women that’s filled with pro-woman axioms like this one: “Masculinity tends to fill a room; femininity to furnish it.”

Yin and Yang

When I emailed Tom the other day requesting clarification on where his gender philosophy stands today, on the cusp of his eighty-second birthday, he sent the following reply:

As is well established by now, human males have, in general, pretty much been in charge of everything over the past 200 millennia, and have pretty much screwed everything up.

The legacy is legion—amassing and misusing personal power, carrying greed to ever new heights, disenfranchising and marginalizing women, waging endless war, imagining ever-more-lethal weapons for waging ever-more-endless war, pushing whole species into extinction, inventing homophobic and misogynist religions, carrying on blood feuds, allowing millions of children to perish of starvation and preventable disease, normalizing rape, degrading the environment, begetting and then abandoning legions of ‘fatherless’ children—and that’s just for starters!

The underlying problem, given the consistency of this sad legacy, not to mention its enormity, would seem to be inherent to the Y chromosome, which, although puny in physical size relative to its Queen Bee counterpart, the X chromosome, is disproportionate in its predisposition for wreaking havoc upon all “the fish of the sea . . . the fowl of the air, and . . . every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

To some, these spirited remarks might sound like the ravings of a misandrist, but if my father truly hated the male sex, I would have felt it growing up, and I never did. My adult gender identity is innocently uncomplicated, and my dad deserves a lot of credit for this. By exposing me to a critique of manhood that fell well short of misandry, he allowed me to become the kind of man that came naturally instead of problematizing my masculinity in one way or another.

In my father’s reckoning, men are not bad so much as they are unbalanced. And if that’s the case, then the solution to the problem is not extermination but rebalancing. Tom’s greatest novel, Poor Richard’s Lament, envisions another kind of father, Benjamin Franklin, returning to Earth in 2011 to confront what’s become of the country he fathered. The novel brilliantly connects macrocosmic societal problems such as inequality, racism, and environmental destruction to the microcosm of Franklin’s heartbreaking neglect of his wife and children, portraying both as pathological imbalances between yin (female energy) and yang (male energy). Franklin’s experiences in modern America and on trial in the Celestial Court of Petitions leave him a changed man, filled with regret but more complete.

Becoming a Whole Man

I mentioned that Tom’s new novel is highly autobiographical. But the plot of Road to Redemption diverges from my father’s story when Cooper McKenzie is diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease at age thirty-eight. Faced with a cruelly premature death, Cooper resolves to seek redemption for his many perceived failings—symbolized by his failure to complete the four-mile timed run on Coronado Island due to untreated cellulitis in both feet—by training for the 1983 Boston Marathon.[1]

I dare say this was a typically male response to the prospect of an early demise—an outward-looking effort to set things right by slaying a symbolic dragon. Running the Boston Marathon (which Cooper does wearing knee and elbow pads and a helmet because by this time his legs have withered to toothpicks and he falls a lot) is not the only measure he takes to find peace while there’s still time, however. He also heeds the advice of his wife, Tessa—the true hero of the novel, portrayed as a three-dimensional human rather than as a flat, angelic feminine archetype—and hires a psychotherapist to help him work through the trauma inflicted upon him in his youth by male family members. Given that women are more than twice as likely as men to seek this kind of help, it’s fair to characterize the choice as a step away from yang toward yin. I don’t want to give away too much because I want you to read the book, but I will say that Cooper’s therapist, George, is effective in his role largely due to his own healthy masculinity.

Like Tom, I believe that every woman has a masculine side and every man a feminine side. The problems come when men feel compelled to deny and reject the yin in them instead of embracing it. Real men—or whole men, I should say—are strong, and strong men are not afraid to dream of being reincarnated as a chickadee.

* * *

If you’d like to read a novel about running, mortality, and redemption that is also a story about what it looks like to become a whole man who’s at peace with himself in a society that makes this very difficult, grab your copy of Tom Fitzgerald’s Road to Redemption today.

[1] N.B. Tom himself completed the run successfully despite his cellulitis and graduated from SEAL training in September 1967, then went straight to Vietnam.

Thank you, Matt. I'll be looking for your father's books.

Best to you and your loved ones.