Radical Pragmatism

In the process of chasing your athletic goals, are you doing what actually works or what you want to work?

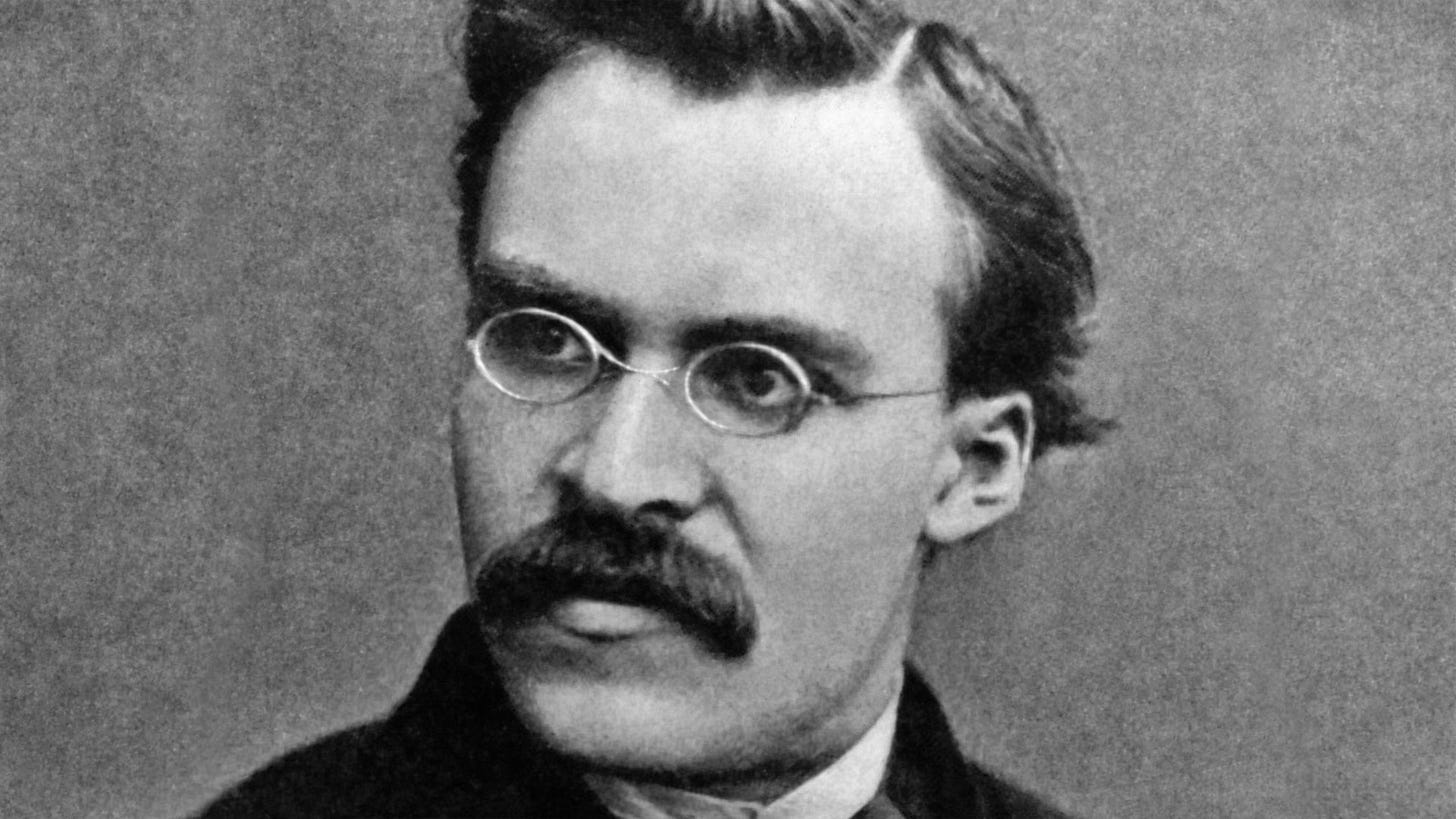

“Many are stubborn in pursuit of the path they have chosen. Few in pursuit of the goal.” —Friedrich Nietzsche

Dictionary.com defines “pragmatism” as “character or conduct that emphasizes practicality.” Pragmatists try to do things in the most effective or efficient way possible. As such, they are distinct from traditionalists, who do things the way they’ve always done them, efficient or not, and ideologues, who do things in what they consider the proper way, effective or not.

An example of a traditionalist is a baker who insists on hand-whipping the eggs she puts in her French silk pie, claiming the old-school method results in better texture, when in fact her customers can’t tell the difference, and if she used an electric eggbeater she could satisfy twice as many customers in half the time.

An example of an ideologue is a politician whose solution to the “crime problem” is to hire more police officers and stiffen penalties, even though all available evidence indicates that efforts to reduce economic disparities are far more effective in reducing crime.

The difference between tradition-based decisions like hand-whipping eggs and ideology-based decisions like electrocuting murderers, on the one hand, and pragmatic decisions like using an eggbeater and creating economic opportunity, on the other hand, is rationality. Tradition and ideology are forms of bias. The pragmatic orientation is an effort to overcome bias and choose what actually works best rather than what a person wants to work.

There’s no law against allowing yourself to be guided by tradition or ideology, but as an endurance athlete you should know that the most successful racers are not just pragmatists but radical pragmatists. Read on.

Means Attachment

All of us are at least somewhat prone to making tradition-based and ideology-based choices. But pragmatists at least try to make rational choices, and are quick to pivot when they realize that the thing they wanted to work isn’t actually working, whereas a lot of athletes are “stubborn in pursuit of the path they’ve chosen,” as Nietzsche put it, continuing in the wrong direction even after it’s become obvious they’re off course.

Some years ago, I coined the term “means attachment” in reference to this phenomenon. All athletes set goals and choose methods, or means, of achieving them. Pragmatists are attached to their goals, not their methods, and will readily abandon a chosen method that isn’t working. Other athletes may start off being attached to their goals, but somewhere along the way they become attached to their chosen means, sticking with them despite clear indications that they will never achieve their goal unless they abandon them favor of a more effective method.

You might recall that in the 2010’s, a whole slew of new runners set performance goals such as qualifying for the Boston Marathon and chose to pursue these ends through a questionable combination of current fads: low-volume, high-intensity interval training (HIIT); CrossFit; barefoot running; and a Paleo diet. It was a terrible choice of path, but many stayed on it long after it was clear they were way off course. That’s means attachment.

The Super Champions

I mentioned above that the most successful athletes are radical pragmatists. Proof comes from a 2017 study by Matthew Barlow and colleagues at Bangor University, who interviewed 32 world-class British athletes about various psychodynamic aspects of their approach to performance. Half of these athletes were classified as champions by virtue of having qualified for Olympic or world championship events, the other half as super champions by virtue of having won multiple Olympic or world championship medals. Several key differences were noted in the super champions, including a trait described as “ruthlessness and/or selfishness in the pursuit of their sporting goals.”

Putting aside the negative connotations associated with the words “ruthless” and “selfish,” what we’re talking about here is a kind of radical pragmatism, where athletes show no loyalty to any particular path toward success but instead manifest an unyielding “whatever works” attitude toward getting where they want to go. Unlike most athletes, they never take two steps in the wrong direction. If they try something and it’s clear after one step that it’s not working, they abandon it and pivot.

An example is Simon Whitfield, who won a gold medal for Canada in the 2000 Olympic men’s triathlon, then promptly overhauled his swim training in an effort to stay on top of the podium. But it was the wrong path, as he would later realize.

“With all the best intentions,” Whitfield told me in an interview for Triathlete, “we had made our swimming program very complex. There were constant meetings among the three coaches on deck. There were charts and heart rates and lactate levels and test sets. There was an underwater camera. We had all this knowledge. Of course this was going to work! We had a theory. We had very bright people implementing it. We had more meetings than you could shake a stick at. But at the end of the day, it was just a failed model.”

Another athlete in Whitfield’s place would have fallen victim to the sunk-cost fallacy and persisted in the method, but super champion that he was, Whitfield himself did not. “I had been a major pusher of this approach,” he confessed to me, “but a year after the Olympics I was able to swallow my pride and say that I was wrong. We had totally overcomplicated it.” So he went back to basics in his swim training, and the result was another medal—silver this time—at the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing.

Embracing Uncertainty

I am not a super champion, but I take my cues from them, and I’m trying to be radically pragmatic as I navigate my present comeback from chronic illness. There are certain practices that I would like to work, such as running twice a day, but are clearly no-go’s given the state of my body, so I’m giving them a pass. Meanwhile, there are certain other practices, such as vagus nerve stimulation, that I’d rather do without, but they clearly are effective, so I’m sucking it up and making use of them.

As I’m writing this, I’m realizing that an athlete must be comfortable with uncertainty to practice radical pragmatism. Most humans are instinctively uncomfortable with uncertainty, which is why most athletes function as traditionalists or idealogues and not as pragmatists in the pursuit of fitness and performance. Instead of admitting they don’t know what works and must therefore take it upon themselves to discover what does, they pretend they do know that whatever tradition or ideology they currently cling to works better than any possible alternative. For them, staying loyal to a flawed approach is preferable to going through a period of uncertainty in the search for a flawless approach.

I’m not going to make this mistake as I continue my quest to become one of the best runners my age. The latest evidence suggests that my current approach is working pretty well but not flawlessly. I’ve gained a ton of fitness in the past few months, but I experience too many bad runs and between runs I feel more run-down and beat-up than I should. I don’t yet know what a flawless approach looks like for me at this stage, but I do know that radical pragmatism will reveal it to me in due time.

Great post as another masters runner I definitely appreciate your advice

You keep popping up in my journey, thank you for what you do.