Figure It Out

Endurance training, when done right, is a continuous process of creative problem solving.

Recently I suffered a setback in my training for the Javelina Jundred, a 100-mile trail race that will be my longest run ever if I complete it. At first I thought it was just another injury—specifically, a flareup of chronic tendonitis in my left hip that forced me to pull the plug on my running three weeks ago—but I’ve since concluded that the problem was much bigger.

For several weeks prior to that final straw I experienced severe and unremitting delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) throughout my legs. The intensity and location of the discomfort changed from day to day, but it never went away. Like a lot of runners, I’m accustomed to being sore somewhere most of the time; never before, however, had I felt so uninterruptedly broken down and beat-up.

Though duly bothered by the phenomenon, I took no practical measures to address it. As long as I could keep running, was my attitude, I could tune out the pain and focus on executing my workouts and stacking fitness. But then all of a sudden I couldn’t run, arrested by a worm-size squeaky wheel on the left side of my groin, at which point I began to see the pattern in a different light. It was obvious to me now that I’d gone off track in my training well before my injury declaration, which meant that allowing the tendon to calm down and then going right back to training the way I was leading up to injury would solve nothing. Quite apart from getting past the immediate crisis, I needed to modify my future training in a manner that did not leave me feeling like I’d just fallen off the back of a truck all day every day.

Three Hypotheses

Whenever an athlete gets injured, it behooves them to figure out why. Doing so won’t change the past, but if the true cause is identified, measures can be taken to keep the same problem from recurring. In the case of my hip injury and the out-of-control DOMS that preceded it, I saw three potential causes:

Age: In the weeks before my breakdown, when my training was going well, I kept increasing my workload, remembering how much I used to train before long COVID and wanting to get back to that level, or at least close to it. But I was five years older than when I got sick, and perhaps it wasn’t realistic to reach for prior standards.

Overtraining: Another possibility was that I had simply done too much too soon, and that if I’d ramped up more slowly, I could have safely approached the training loads I was accustomed to handling in the Before Times. This theory was supported by the fact that my legs remained incredibly sore for ten full days after I stopped running, indicating that my neuroendocrine system had passed a tipping point, as happens with overtraining syndrome.

Long COVID: Though healthier than I’ve been in a very long time, I still experience daily reminders that my body continues to harbor the chronic disease that turned my world upside down beginning in October 2020. Among its myriad effects, Long COVID essentially lowers an athlete’s threshold for overtraining by causing the sympathetic nervous system to panic prematurely in response to perceived threats such as heavy endurance training. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that my DOMS was combined with a resurgence of neuropathy, a classic long COVID symptom that plagued my first two years with the illness but had since abated.

Testing, Testing

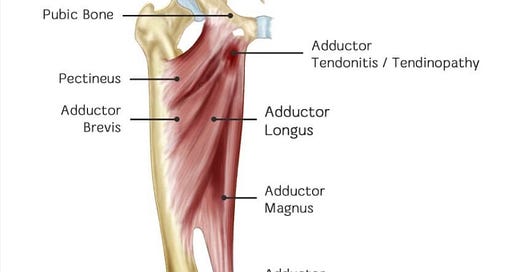

For the first week after I declared myself injured I replaced all of my runs with ElliptiGO rides and incline treadmill walks while strength training as normal. This allowed me to disentangle the effects of running from those of strength training on my muscle soreness. Throughout that week, the specific muscles I hit the hardest in the gym (quads, hamstrings, hip adductors) hurt like hell while other running muscles (hip flexors, calves, returned to baseline), leading me to conclude that, for whatever reason, strength training was the primary cause of my symptoms, running at most a minor contributor.

To test the hunch, I replaced my normal strength workouts with lighter alternatives, and what do you know? The soreness in my thighs quickly abated, confirming the hunch. I couldn’t explain why my body had suddenly lost its tolerance for lifting weights, and I wasn’t happy about it. Unlike a lot of runners, I actually enjoy working hard in the gym, and I’m fully convinced of the benefits. Be that as it may, it was clear that a minimalist approach to strength training would have to be among the modifications I made to my training to stay on track for Javelina.

My next test was a very cautious 10K jog, which I undertook last Friday, three weeks to the day after I bailed out of my last run. Braced for disappointment, I breathed a huge sigh of relief when the ache in my left hip adductor tendon leveled off below the threshold of tolerability.

Now what? Another test, of course! I now have 15 weeks to regain my momentum and prepare for my 100-miler. For the next several weeks, I will experiment with a more cautious approach to training, running every second day, avoiding faster running, continuing to do a fair amount of nonimpact cross-training, taking it easy in the gym, and prioritizing my weekend long runs. In this manner I hope to build the endurance I need to go the distance at Javelina while preserving my beleaguered legs.

Assuming this process goes well, I will either increase the frequency of my runs or incorporate workouts at higher intensities or both in the final weeks before my taper. In the past I’ve found that piling on the stress for a short period of time yields rapid gains in fitness without putting my body over the edge, especially if I’m vigilant in looking out for warning signs and responsive when they appear. With me there’s always the temptation to push for more, but a timely setback like the one I’ve just emerged from generally supplies the restraint I need to avoid getting carried away.

Creative Problem Solving

In endurance training there are always problems. Sometimes they’re as big and blatant as a showstopping injury, other times as small and subtle as avoiding an early peak when your training is going “perfectly” and you’re ahead of schedule. At no time, however, are things truly perfect and not in need of tinkering.

To complicate matters, problems affecting endurance training are often difficult to diagnose, have no obvious cause, and present no clear solution. They’re messy, in other words, and require acceptance of uncertainty and a creative approach on the part of the problem solver. Instead of just following a plan that is assumed to be perfect you are continuously in the process of figuring out how to train. This is as true for the guy who’s been at it for 43 years and written 36 books on endurance sports as it is for the newbie. I hope the foregoing example of creative problem solving gives you inspiration for figuring out your next challenge.